-

Global Head of Research and Strategy Brian Klinksiek (L) and Canada Head of Research and Strategy Chris Langstaff (R) discuss how rising mortgage rates will impact the residential real estate market.

In recent editions of LaSalle Macro Quarterly (LMQ), many charts have highlighted interest rate rises. LaSalle has especially focused on the repricing of income-producing real estate that rate rises have triggered in much of the globe. But the spike in rates is also having an impact on owner-occupied residential real estate, which accounts for a much larger share of the global property pie than do institutional assets. As we release the LMQ for Q3 2023, we look at the broad implications of higher residential mortgage rates, and how they vary by country. Even if institutional investors do not directly touch owner-occupied housing, they should consider the risks (and a few opportunities) caused by these dynamics.Higher residential mortgage rates have implications for both new buyers and existing owners. For new buyers, higher rates reduce the purchase price they can pay (assuming a fixed amount of debt service). In practice, buyers cope with this by dedicating a larger share of their income to housing, or by scaling back or postponing their home purchase ambitions. For economies in which housing constitutes a meaningful share of the economy, this can create a noticeable drag on GDP growth. It may also put downward pressure on home prices, which can have indirect wealth effects on consumer spending. (So far, house prices for key countries have held up reasonably well during this period of rising rates—as shown in the chart on page 7 of the LMQ—but risks remain.)

For existing owners, much depends on the specific terms of the mortgage. The US mortgage market is unique globally in having a very large share of loans with rates that are fixed over a fully amortizing term (typically 30 years), according to data from Fitch. Assuming they do not move, borrowers can continue to enjoy low fixed payments. Elsewhere in the world, residential mortgage rates are usually floating or fixed only for a limited time. When rates rise, they filter through to borrowers gradually as fixed rate periods end—in other words, when rates reset. Depending on the mechanism for rate resets, they can cause a direct hit to disposable incomes. Households may react to this by scaling back spending elsewhere, or in the extreme, leaving the ranks of homeownership. These impacts will be more significant in places where consumers already have a high debt service burden.

For investors in income-producing institutional real estate, there are two aspects of these dynamics that are especially relevant. One is the broad recession risk that comes from weaker housing markets and stretched consumers. Oxford Economics has cited differential exposures to mortgage resets as a driver of divergence in near-term economic growth between the US and Canada. Second, the substitution effect from owned to rented housing may provide a boost to both multifamily and single-family rental demand, potentially driving stronger performance for residential strategies.

Canada: An illustrative case

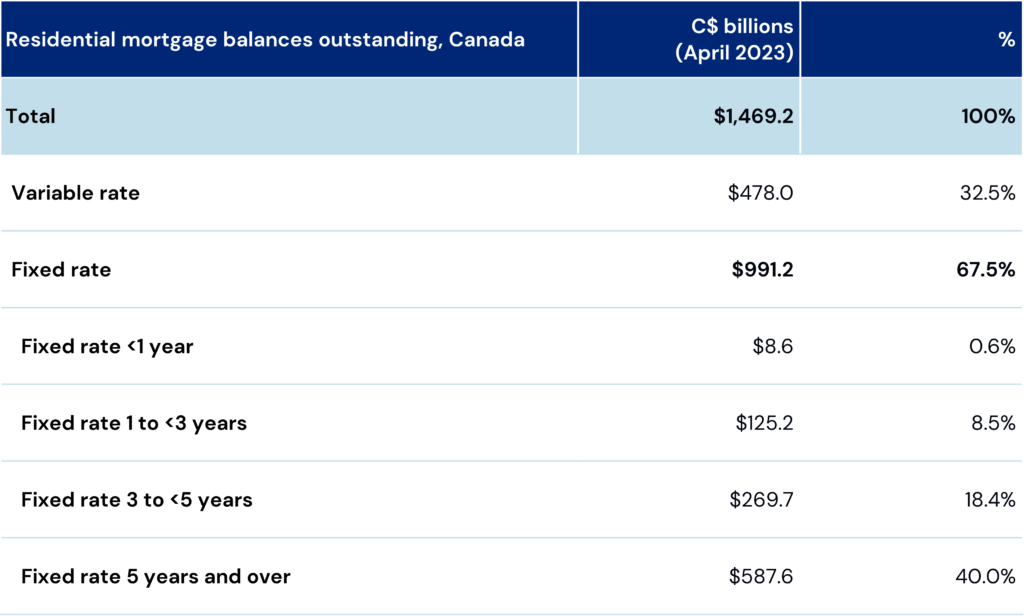

Canada is an interesting case study because the structural characteristics of its residential mortgage market and the availability of transparent data permit a relatively clear identification of mortgage rate resets. Most residential mortgages in Canada have 25- or 30-year amortization periods, with typical fixed rate periods (known as “terms”) running from as short as one year to as long as ten years, according to the Bank of Canada. Some mortgages have a fixed interest rate that is reset for the next term according to the prevailing market rate. This occurs through a renewal at the end of each term, until the mortgage is fully paid off. According to Bank of Canada (see table), fixed-rate mortgages account for two-thirds of balances outstanding in the country among lenders. Most fixed-rate mortgages have remaining terms of five years or more (40% of overall balances), followed by three-to-five years at 18.4%. Only 8.5% of all fixed-rate mortgages expire in the next three years

Composition of outstanding residential mortgage balances, Canada (April 2023)

Sources: Bank of Canada, LaSalle. Data as of April 2023.

However, the remaining one-third of Canadian mortgages are variable rate, which float based on short-term interest rate movements. The Bank of Canada has hiked interest rates nine times since March 2022, pushing up rates on some variable-rate mortgages to around 6.0%, from roughly 2.8% a year ago. The most common type of variable-rate mortgages in Canada have fixed monthly payments. As interest rates rise, a higher proportion of the payment goes toward interest and less toward principal. Rising rates over the past 18 months have put some borrowers in the position of having monthly payments that do not cover the interest portion of the mortgage. The excess (unpaid) interest for that month gets added to the principal, increasing the original mortgage amount. Compared to countries where the absolute monthly payment amount adjusts directly with rates, this mechanism prevents an immediate near-term hit to disposable income from rising rates. But it does effectively embed the impact of higher rates into a longer-term increase in debt on household balance sheets.The rest of the world

Beyond Canada, which countries are impacted by rising residential mortgage rates? Cross-border comparisons are not straightforward; the devil is in the detail. Nuances to consider include variation in fixed-rate terms, amortization periods, interest rate levels, and when and how rates reset. Many factors, including macro indicators like household debt levels and the structure of countries’ residential mortgage markets, need to be considered in assessing a market’s exposure.

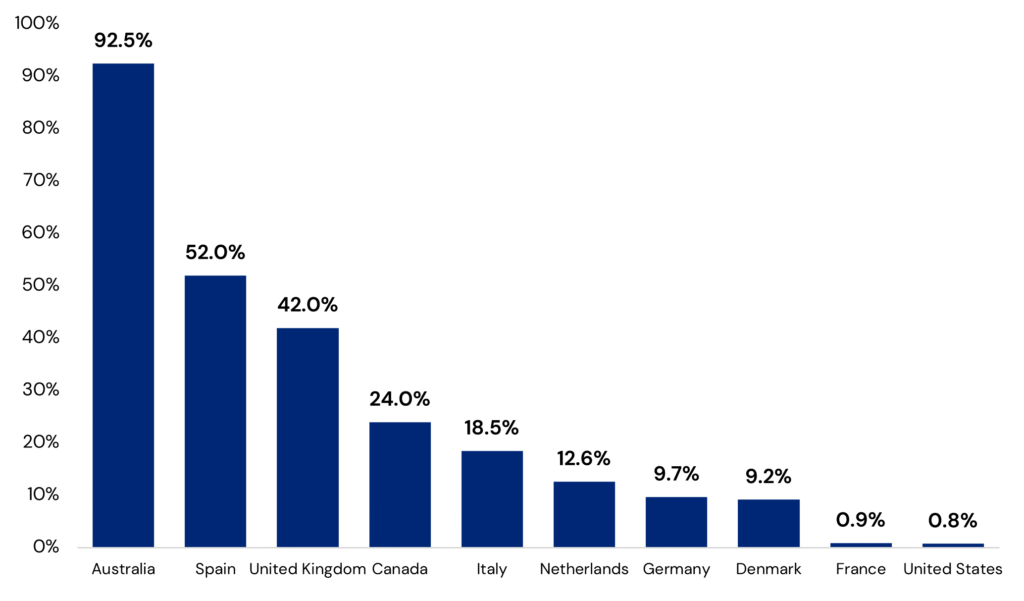

One persistent issue is that data on the relative shares of fixed- versus variable-rate mortgages by country tend to classify any mortgage as fixed rate if it is fixed for a period of time, even if it that rate will reset in the near term. Analysis by Fitch Ratings attempts to correct for this with a metric that includes any mortgages with rates that are expected to expire or reset within 24 months. On this analysis, Australia leads in exposure to resets, followed by Spain, the UK, and Canada. Australian mortgages with fixed rates generally have shorter fixed-rate periods of around two years; this compares with five years in the United Kingdom and Canada, and 30 years in the U.S. (Although not in the Fitch dataset, we understand that Sweden is also relatively highly exposed to resets.)

Share of residential mortgages originated with rates that expire or reset within 24 months

Expressed as % of 2020 loan originations. Analysis as of December 2022.

Sources: Fitch RatingsFitch extended their analysis to combine and layer in pre-reset mortgage debt-service-to-income (“DTI”) ratios by country. This allowed them to estimate how much an increase in DTIs would be caused by a five-percentage point increase in interest rates. They found that the impact roughly followed the rank ordering above, with Australia and the UK most exposed, and the US least exposed. It should be noted that many of the same mitigating factors that apply to Canada (e.g., strong immigration, shortages of housing, low mortgage arrears) also apply to Australia, Spain and the UK.

The outlier case of the US is not quite as positive as it may appear. As a country with high internal mobility and (unlike many other markets) mortgages that are not “portable” between different collateral, the effective exposure of US households to mortgage rate changes is probably higher than implied by these data alone. Moreover, there are some downsides to having a large share of long, fixed rate mortgages. For one, the lesser impact of higher rates on consumer spending potentially requires more interest rates increases to have the same desired impact on inflation. Another factor, which is already evident, is that having a low interest rate locked in creates a barrier to moving, limiting the supply of housing for sale and making home prices sticky.

Looking ahead

- As mortgages reset at higher rates, a greater share of household budgets will be diverted to mortgage payments. This could be particularly acute for households that live “paycheck to paycheck.” While some households may have excess savings to cushion the blow of higher mortgage payments, overall discretionary retail spending is at risk of moving lower. This, in turn, could impact retail real estate market fundamentals. The composition of retail spending could also shift, as households with lower discretionary incomes move more of their spending to discount retailers, and away from discretionary or luxury items. In the case of Canada, Oxford Economics forecasts that consumer spending will drop 1.8% from its pandemic-era peak, potentially tipping the economy into recession.

- While interest rate hikes since early 2022 have increased financing costs for owners of multifamily apartments and reduced transaction volumes, ongoing housing shortages in various countries are contributing to higher apartment demand. With higher mortgage payments putting the cost of home ownership out of reach for many, demand for relatively lower-cost rental housing has increased. This has clearly been the case in Canada, where according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, apartment vacancy declined by 120 basis points in 2022 as apartment absorption reached an all-time high of 100,300 units, an increase of 59% over 2021.

Sources:1. ECONOSIGHTS: Three reasons why Australia is more vulnerable to higher rates – Mousina, Diana, AMP Capital, September 2022.

2. Fear of Renewal: Most new homebuyers ‘very worried’ next term will bring much higher monthly payments – Angus Reid Institute, May 2023

3. How Do Mortgage Rate Resets Affect Consumer Spending and Debt Repayment? Evidence from Canadian Consumers – Bank of Canada, May 2020

4. Statistics on Mortgage Arrears in Canada – Canadian Bankers Association, Table DB50 Public, June 2023

5. Global Housing and Mortgage Outlook – 2023 – Fitch Ratings, December 2022

6. Mortgage Interest Payments in Advanced Economies – One Channel of Monetary Policy – Reserve Bank of Australia, Statement on Monetary Policy, February 2023

Important Notice and Disclaimer

This publication does not constitute an offer to sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or any interests in any investment products advised by, or the advisory services of, LaSalle Investment Management (together with its global investment advisory affiliates, “LaSalle”). This publication has been prepared without regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of recipients and under no circumstances is this publication on its own intended to be, or serve as, investment advice. The discussions set forth in this publication are intended for informational purposes only, do not constitute investment advice and are subject to correction, completion and amendment without notice. Further, nothing herein constitutes legal or tax advice. Prior to making any investment, an investor should consult with its own investment, accounting, legal and tax advisers to independently evaluate the risks, consequences and suitability of that investment.

LaSalle has taken reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this publication is accurate and has been obtained from reliable sources. Any opinions, forecasts, projections or other statements that are made in this publication are forward-looking statements. Although LaSalle believes that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, they do involve a number of assumptions, risks and uncertainties. Accordingly, LaSalle does not make any express or implied representation or warranty, and no responsibility is accepted with respect to the adequacy, accuracy, completeness or reasonableness of the facts, opinions, estimates, forecasts, or other information set out in this publication or any further information, written or oral notice, or other document at any time supplied in connection with this publication. LaSalle does not undertake and is under no obligation to update or keep current the information or content contained in this publication for future events. LaSalle does not accept any liability in negligence or otherwise for any loss or damage suffered by any party resulting from reliance on this publication and nothing contained herein shall be relied upon as a promise or guarantee regarding any future events or performance.

By accepting receipt of this publication, the recipient agrees not to distribute, offer or sell this publication or copies of it and agrees not to make use of the publication other than for its own general information purposes.

Copyright © LaSalle Investment Management 2023. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced by any means, whether graphically, electronically, mechanically or otherwise howsoever, including without limitation photocopying and recording on magnetic tape, or included in any information store and/or retrieval system without prior written permission of LaSalle Investment Management.

Nov 19, 2024

ISA Outlook 2025

Shifting interest rates, dynamic occupier fundamentals, deepening bifurcation within sectors: how should real estate investors respond?